Learning Python with Advent of Code Walkthroughs

Dazbo's Advent of Code solutions, written in Python

Advent of Code 2025 - Day 11

Useful Links

Concepts and Packages Demonstrated

Problem Intro

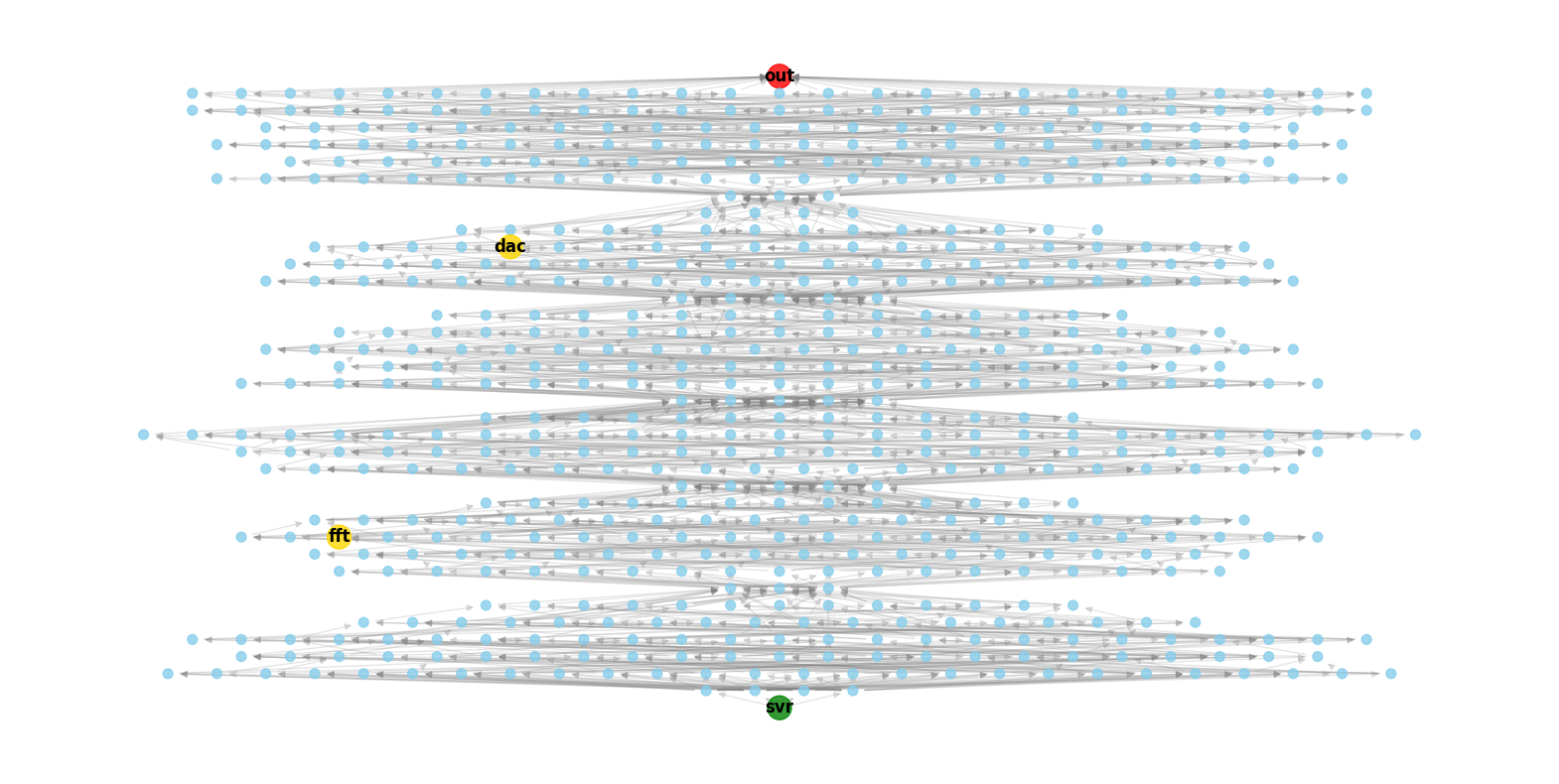

So… we’re connecting a server rack to a reactor. Classic Thursday in the Advent of Code universe. We are given a list of devices and their outputs, which forms a network. Data only flows one way (a Directed Acyclic Graph, or DAG).

The input looks like this:

aaa: you hhh

you: bbb ccc

bbb: ddd eee

ccc: ddd eee fff

Part 1: Trusty NetworkX

Find the number of unique paths from you to out.

I’ve used NetworkX a lot before, and it’s perfect for this. Why re-invent the wheel when you have a library that speaks “Graph” natively?

First, we parse the input into a list of edges. NetworkX expects a list of (source, target) tuples.

def parse_input(data: list[str]) -> list[tuple[str, str]]:

""" Parse the input into a list of edges. I.e. (device, output) """

edges = []

for line in data:

device, outputs = line.split(":")

for output in outputs.split():

edges.append((device.strip(), output.strip()))

return edges

Then, Part 1 is trivial thanks to nx.all_simple_paths(). This function returns a generator of all paths between a source and a target. Since the number of paths is small, we can just list them and count them.

def part1(data: list[str]):

edges = parse_input(data)

graph = nx.DiGraph(edges)

# NetworkX makes this far too easy!

paths = list(nx.all_simple_paths(graph, source="you", target="out"))

return len(paths)

Part 2: I’ve Got a Bad Feeling About This

Find the number of paths from svr to out that traverse **both dac and fft.**

So, for Part 2, the requirements changed slightly. We start at a different node (svr) and need to visit dac and fft before hitting out.

My first thought? “Re-use part 1! Just get all paths from svr to out and filter for the ones containing dac and fft.”

I had a feeling this wasn’t going to work…

It turns out that with the real input (over 600 nodes), the number of paths is astronomical. My code just sat there, presumably calculating the heat death of the universe. This is a classic Combinatorial Explosion. We can’t list all the paths; we just need to count them.

Optimisation 1: Smaller Paths

We can break the problem down. There are two valid sequences to visit our mandatory stops:

svr->dac->fft->outsvr->fft->dac->out

We can count the paths for each segment independently and multiply them. So, for sequence 1:

Total Paths = (svr->dac * dac->fft * fft->out)

Optimisation 2: Memoisation

But even calculating svr->dac was taking too long with simple enumeration. We need Memoization, and I’ve implemented this with a recursive Depth First Search (DFS) that caches the result for each node.

(We used this exact technique recently in Day 7 to count quantum timelines! Have a look at that walkthrough for a more in-depth explanation of how it works.)

def count_paths_between(graph: nx.DiGraph, start_node: str, end_node: str) -> int:

"""

Count unique paths from start_node to end_node using recursion and memoization.

"""

@cache

def _count(current: str) -> int:

""" Inner function used because the graph itself is unhashable. """

if current == end_node: # A valid path was found

return 1

count = 0

# Sum the paths from all neighbours

for neighbor in graph.neighbors(current):

count += _count(neighbor)

return count

return _count(start_node)

Why the Inner Function?

You might wonder why I defined _count inside count_paths_between.

The @cache decorator works by using the function arguments as a dictionary key to store the result. If we put @cache on the outer function, Python would try to hash the graph object. But nx.DiGraph is mutable and therefore unhashable — trying to cache it throws a TypeError.

By using an inner function, _count only takes a string (current) as an argument. Strings are hashable, of course! The inner function “closes over” the graph variable from the outer scope, allowing us to access the graph without needing to pass it (and try to hash it) in every recursive call. It’s a neat pattern for caching things.

Results

The output looks something like this:

Part 1 soln=543

Part 2 soln=987654321098765

Part 1 with NetworkX runs in about 0.005s. And Part 2 - with memoisation - runs in about 0.004s, despite being a much larger problem space.