Learning Python with Advent of Code Walkthroughs

Dazbo's Advent of Code solutions, written in Python

Advent of Code 2015 - Day 21

Useful Links

Concepts and Packages Demonstrated

DataclassRegexsplatClassesCartesian ProductList comprehensionLambda function

Page Navigation

Problem Intro

We need win an RPG computer game match.

We alternative taking turns with the CPU. The CPU is playing the boss. The current player attacks on their turn.

- The attack reduces the opponent’s hit points.

- The loser is player whose hit points reach 0 (or lower).

Damage taken = attacker's damage - defender's armor, with a minimum of 1.- Damage and armor score start at 0 and can be increased by buying items from the shop, in exchange for gold. Gold is unlimited.

The shop’s products are given to us:

Weapons: Cost Damage Armor

Dagger 8 4 0

Shortsword 10 5 0

Warhammer 25 6 0

Longsword 40 7 0

Greataxe 74 8 0

Armor: Cost Damage Armor

Leather 13 0 1

Chainmail 31 0 2

Splintmail 53 0 3

Bandedmail 75 0 4

Platemail 102 0 5

Rings: Cost Damage Armor

Damage +1 25 1 0

Damage +2 50 2 0

Damage +3 100 3 0

Defense +1 20 0 1

Defense +2 40 0 2

Defense +3 80 0 3

Shop rules:

- We must buy exactly one weapon.

- We can buy one armor item.

- We can buy 0, 1, or 2 rings.

- The shop only has one of each item.

We start with 100 hit points. Our damage and armor scores are given by the sum of the respective values of the items we have bought. Our opponent’s starting hit points, damage and armor scores are given to us as input. E.g.

Hit Points: 104

Damage: 8

Armor: 1

Part 1

What is the least amount of gold you can spend and still win the fight?

Let’s start with the easy part: reading in the shop information. I copied the shop text into a file, because I didn’t know if the shop data might change for Part 2.

First, I create a dataclass to store each row read from the file.

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class Item:

""" Immutable class for the properties of shop items """

name: str

cost: int

damage: int

armor: int

Then, I read the shop data using regex, as follows:

def process_shop_items(data) -> tuple[dict, dict, dict]:

""" Process shop items and return tuple of weapons, armor and rings.

Each tuple member is a dict, mapping a shop item to its properties (name, cost, damage, armor).

Args:

data (List[str]): Lines from the shop file

Returns:

Tuple[dict, dict, dict]: Dictionaries of weapons, armor and rings.

Each dict is a mapping of item name to an Item object.

"""

# e.g. "Damage +1 25 1 0"

item_match = re.compile(r"^(.*)\s{2,}(\d+).+(\d+).+(\d+)")

weapons = {}

armor = {}

rings = {}

block = ""

for line in data:

if "Weapons:" in line:

block = "weapons"

elif "Armor:" in line:

block = "armor"

elif "Rings:" in line:

block = "rings"

else: # we're processing items listed in the current block type

match = item_match.match(line)

if match:

item_name, cost, damage_score, armor_score = match.groups()

item_name = item_name.strip()

cost, damage_score, armor_score = int(cost), int(damage_score), int(armor_score)

if block == "weapons":

weapons[item_name] = Item(item_name, cost, damage_score, armor_score)

elif block == "armor":

armor[item_name] = Item(item_name, cost, damage_score, armor_score)

elif block == "rings":

rings[item_name] = Item(item_name, cost, damage_score, armor_score)

return weapons, armor, rings

The regex works as follows:

^denotes the start of the line.(.*)captures any sequence of characters. The.*means “any character (.) repeated zero or more times (*)”. The parentheses are used to create a capturing group, which allows this sequence of characters to be extracted later. This is how we capture the name of the item.\s{2,}matches two or more whitespace characters.\srepresents a whitespace character and{2,}means “match at least 2 of the preceding element”. This allows the pattern to skip over an area of the string that contains at least two spaces.(\d+)captures one or more digit characters.\drepresents any digit (0-9) and+means “one or more of the preceding element”. This is another capturing group, and is used to capture theCost..+(\d+).(+\d+)matches one or more of any character (which is ignored), followed by one or more digits, followed again by one or more of any character (which is ignored), and finally ending with one or more digits. The digits are expected to be captured. They represent theDamageandArmor.

We read the input file one line at a time. And whenever we read a “header” row (i.e. containing Weapons, Armor, or Rings), we set a variable accordingly, and use this to add all subsequent items found to the appropriate dictionary. In each case, we take the current row, and use it to build an Item object, containing the attributes for a given item. We return the results as a tuple of three dictionaries.

We call this from our main() method like this:

# Shop contructor takes multiple params. Splat the tuple to pass these in.

shop = Shop(*process_shop_items(data))

This line is interesting, because I’m using the splat operator to unpack the returned tuple to its three constituent dictionaries, and passes these into the __init__() method of our my Shop class. More on that class later.

Now, let’s look at my Loadout class:

class Loadout:

""" A valid combination of weapon, armor, and rings. """

def __init__(self, item_names: list, items: list):

""" Initialise a loadout.

Args:

item_names (list): A list of item names

items (list): _description_

"""

self._item_names = item_names # E.g. ['Dagger', None, 'Damage +1', 'Damage +2']

self._items = items # The Items

self._cost = 0 # computed

self._damage = 0 # computed

self._armor = 0 # computed

self._compute_attributes()

@property

def cost(self) -> int:

return self._cost

@property

def damage(self) -> int:

return self._damage

@property

def armor(self) -> int:

return self._armor

def _compute_attributes(self):

""" Compute the total cost, damage and armor of this Loadout """

an_item:Item

for an_item in self._items:

self._cost += an_item.cost

self._damage += an_item.damage

self._armor += an_item.armor

def __repr__(self):

return f"Loadout: {self._item_names}, cost: {self._cost}, damage: {self._damage}, armor: {self._armor}"

I’ve defined a Loadout to be any valid combination of weapon, armor and rings. (We’ll create the valid loadouts later, in the Shop class.)

A few notes about Loadout:

- When initialising, we pass in a

listof item names, and the correspondinglistof Items. - We then call

self._compute_attributes()to compute the attributes of thisLoadout, i.e. the totalcost,damageandarmorvalues of thisLoadout. Note how this method starts with_, indicating that it is intended to be a private method, and should only be used by the internal implementation of this class. This method should not be called from outside the class. - The

self._compute_attributes()method iterates through theItemobjects, and incrementally updates the attributes each time. Thus, we now know thecost,damageandarmorof eachLoadout. - I expose the

cost,damageandarmorattributes as properties, using the@propertydecorator.

Now let’s look at the Shop class:

class Shop:

""" Represents all the items that can be bought in the shop """

def __init__(self, weapons: dict, armor: dict, rings: dict):

""" Stores all_items as a dict to map the item name to the properties.

Then computes all valid combinations of items, as 'loadouts'

"""

self._weapons = weapons # {'Dagger': Item(name='Dagger', cost=8, damage=4, armor=0)}

self._armor = armor # {'Leather': Item(name='Leather', cost=13, damage=0, armor=1)}

self._rings = rings # {'Damage +1': }

self._all_items = weapons | armor | rings # merge dictionaries

self._loadouts = self._create_loadouts()

def _create_loadouts(self):

""" Computes all valid loadouts, given the items available in the shop. Rules:

- All loadouts have one and only one weapon

- Loadouts can have zero or one armor

- Loadouts can have zero, one or two rings. (But each ring can only be used once.)

"""

loadouts = []

weapon_options = list(self._weapons) # Get a list of the weapon names

armor_options = [None] + list(self._armor) # Get a list of the 6 allowed armor options

# build up the ring options. Start by adding zero or one ring options.

# E.g. [[None], [Damage +1], [Damage +2]...]

ring_options = [[None]] + [[ring] for ring in self._rings]

# And now add combinations (without duplicates) if using two rings

for combo in combinations(self._rings, 2):

ring_options.append([combo[0], combo[1]]) # Append, e.g. ['Damage +1', 'Damage +2']

# Now we have 5 weapons, 6 armors, and 22 different ring combos

# smash our valid options together to get a list with three items

# Then perform cartesian product to get all ways of combining these three lists (= 660 combos)

all_items = [weapon_options, armor_options, ring_options]

all_loadouts_combos: list[tuple] = list(itertools.product(*all_items))

# Our product is a tuple with always three items, which looks like (weapon, armor, [rings])

# Where [rings] can have [None], one or two rings.

# We need to flatten this list, into... [weapon, armor, ring1...]

for weapon, armor, rings in all_loadouts_combos:

# e.g. 'Dagger', 'Leather', ['Damage +1', 'Damage +2']

# Flatten to ['Dagger', 'Leather', 'Damage +1', 'Damage +2']

loadout_item_names = [weapon] + [armor] + list(rings)

# now use the item name to retrieve the actual Items for this loadout

items = []

for item_name in loadout_item_names:

if item_name is not None:

an_item = self._all_items[item_name]

items.append(an_item)

# And build a Loadout object, passing in the item names (for identification) and the items themselves

loadout = Loadout(loadout_item_names, items)

loadouts.append(loadout)

return loadouts

def get_loadouts(self) -> list[Loadout]:

""" Get the valid loadouts that can be assembled from shop items """

return self._loadouts

The interesting thing about this class is the _create_loadouts() method. The goal of this method is to create all the possible Loadout instances that are allowed, according to the rules. It works like this:

- We start with a list of weapons; there are five possible weapons.

- Then we create a list of the armor options. There are six, because

Noneis a valid armor configuration. - Then we determine all the ring combinations that are possible:

- We start with

None, plus the six single ring options. - Then we add the dual ring combinations. There are 15 dual ring combinations.

- We start with

- We take this three lists, and combine them into one list, containing three lists.

- We use

itertools.product()to obtain the cartesian product of combining all the items from these three lists. This returns5*6*22 = 660different combinations of items. - For each combination, we then flatten in a single flattened list.

- We iterate over each item name in the list, and use it to retrieve the matching

Item, and we add thisItemto the list of items that make up thisLoadout. - Finally, we build a valid

Loadoutusing these items, and add it to the list of valid Loadouts that will eventually be returned.

Okay, so now we know every valid combination of items that a player can start out with. Now I create a Player class, which is used to set the player’s initial state. Note that we will always need to define two players:

- Our player. We will want to be able to try various different loadouts, in order to find the loadout that can win for the lowest cost.

- The boss. The stats for the boss are fixed, and are given in our input.

Here’s the Player class I created initially:

class Player:

"""A player has three key attributes:

hit_points (life) - When this reaches 0, the player has been defeated

damage - Attack strength

armor - Attack defence

Damage done per attack = this player's damage - opponent's armor. (With a min of 1.)

Hit_points are decremented by an enemy attack.

"""

def __init__(self, name: str, hit_points: int, damage: int, armor: int):

self._name = name

self._hit_points = hit_points

self._damage = damage

self._armor = armor

@property

def name(self) -> str:

return self._name

@property

def hit_points(self) -> int:

return self._hit_points

@property

def armor(self) -> int:

return self._armor

def take_hit(self, loss: int):

""" Remove this hit from the current hit points """

self._hit_points -= loss

def is_alive(self) -> bool:

return self._hit_points > 0

def _damage_inflicted_on_opponent(self, other_player: Player) -> int:

"""Damage inflicted in an attack. Given by this player's damage minus other player's armor.

Returns: damage inflicted per attack """

return max(self._damage - other_player.armor, 1)

def attack(self, other_player: Player):

""" Perform an attack on another player, inflicting damage """

attack_damage = self._damage_inflicted_on_opponent(other_player)

other_player.take_hit(attack_damage)

def __str__(self):

return self.__repr__()

def __repr__(self):

return f"Player: {self._name}, hit points={self._hit_points}, damage={self._damage}, armor={self._armor}"

It’s fairly self-explanatory.

- It stores the initial stats of the player, i.e. hit points, damage, armor.

- The

take_hit()method reduces our hit points. - The

_damage_inflicted_on_opponent()method calculates the effectiveness of an attack; i.e. the number of hit points that will be reduced bytake_hit(). - Finally, the

attack()method is how a player takes their turn. It calls_damage_inflicted_on_opponent(), and then callstake_hit()against the opponent’sPlayerinstance. - The class has an

is_alive()method to determine if the player has been defeated.

We can read in the boss stats like this:

def process_boss_input(data:list[str]):

""" Process boss file input and return tuple of hit_points, damage and armor """

boss = {}

for line in data:

key, val = line.strip().split(":")

boss[key] = int(val)

return boss['Hit Points'], boss['Damage'], boss['Armor']

And then, in our main() method:

hit_points, damage, armor = process_boss_input(data)

boss = Player("Boss", hit_points=hit_points, damage=damage, armor=armor)

And we can create every possible initial player starting state, like this:

# Get the valid loadouts

loadouts = shop.get_loadouts()

# Create a player using each loadout

for loadout in loadouts:

player = Player("Player", hit_points=100, damage=loadout.damage, armor=loadout.armor)

One way to now solve Part 1 is to simply play the game with each possible player. I.e.

# Create a player using each loadout

for loadout in loadouts:

player = Player("Player", hit_points=100, damage=loadout.damage, armor=loadout.armor)

player_wins = play_game(player, boss)

Then we would need to implement a play_game() function, which returns True if our player is still alive at the end of the game, but False if our player has been defeated. It could look like this:

def play_game(player: Player, opponent: Player) -> bool:

"""Performs a game, given two players. Determines if player1 wins, vs boss.

Args:

player (Player): The player

enemy (Player): The opponent

Returns:

bool: Whether player wins

"""

boss = copy.deepcopy(opponent)

logger.debug("Playing...")

i = 1

current_player = player

other_player = boss

while (player.hit_points > 0 and boss.hit_points > 0):

current_player.attack(other_player)

logger.debug("%s round %d", current_player.name, i)

logger.debug(other_player)

if current_player == boss:

i += 1

current_player, other_player = other_player, current_player

return player.is_alive()

The function works by looping for as long as both players are still alive. As soon as one player has been defeated (i.e. hit points now not greater than 0), then the loop ends, and we return whether our player is alive or not. Note that at the of each loop, we swap the two players around. This is how we alternate who is attacking.

But it turns out this is very inefficient. We don’t actually need to play a complete game for each pairing of player and boss. Instead, we can simply determine how many attacks are needed to defeat a given player, by calculating their starting hit points divided by their opponent’s effective attack damage. If our player needs fewer (or the same) attacks than the boss, then our player will win. (The same number of attacks will win, because our player always goes first.)

So, we need to add these methods to our Player class:

def get_attacks_needed(self, other_player: Player) -> int:

""" The number of attacks needed for this player to defeat the other player. """

return ceil(other_player.hit_points / self._damage_inflicted_on_opponent(other_player))

def will_defeat(self, other_player: Player) -> bool:

""" Determine if this player will win a fight with an opponent.

I.e. if this player needs fewer (or same) attacks than the opponent.

Assumes this player always goes first. """

return (self.get_attacks_needed(other_player)

<= other_player.get_attacks_needed(self))

And now, finally, we can solve for Part 1 efficiently. We update our main() method like this:

# Create a player using each loadout

loadouts_tried = []

for loadout in loadouts:

player = Player("Player", hit_points=100, damage=loadout.damage, armor=loadout.armor)

player_wins = player.will_defeat(boss)

# Store the loadout we've tried, in a list with item that look like [loadout, success]

loadouts_tried.append([loadout, player_wins])

# Part 1

winning_loadouts = [loadout for loadout, player_wins in loadouts_tried if player_wins]

cheapest_winning_loadout = min(winning_loadouts, key=lambda loadout: loadout.cost)

logger.info("Cheapest win = %s", cheapest_winning_loadout)

This code creates a Player for each possible Loadout, and then determines if the player will win against the boss. I save the result with each Loadout in the loadouts_tried list.

We then use a list comprehension to return only winning loadouts. And finally, we use the min() function, and set the key to be a lambda which is defined as the cost attribute of a Loadout instance.

Part 2

What is the most amount of gold you can spend and still lose the fight?

Phew! Given the code we already have, this requires a trivial addition:

# Part 2

losing_loadouts = [loadout for loadout, player_wins in loadouts_tried if not player_wins]

priciest_losing_loadout = max(losing_loadouts, key=lambda loadout: loadout.cost)

logger.info("Priciest loss = %s", priciest_losing_loadout)

It’s the same code as Part 1. But this time, we want all the loadouts where we lost, and then we want to find the one where the cost was highest.

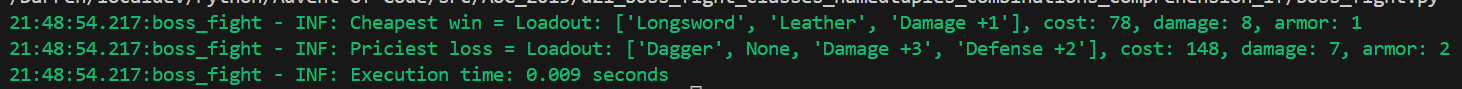

Results

And when we run it…

So, it’s pretty quick.