Learning Python with Advent of Code Walkthroughs

Dazbo's Advent of Code solutions, written in Python

The Python Journey - Opening and Reading Files

Useful Links

Almost every challenge in Advent of Code requires you to read some input data. Perhaps the easiest approach to get this data into your Python program is to simply save the supplied input data as a file. You can then read that file in your program.

Saving Your Files

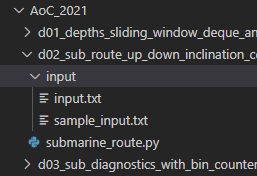

Generally, I like to create two files for each program:

- A file of sample data, which I call

sample_input.txt. Most AoC problems come with some sample data, which is usually much less complex or smaller than the actual data. It’s a good idea to build your solution around that sample data. Get your solution working with the sample data, before progressing to working with the actual data. - A file of actual data, which I call

input.txt. The actual data varies between participants. Consequently, different AoC participants will need to solve the problem using different right answers.

I tend to create blank versions of these files, and then simply copy-paste the data from the browser in to these files.

Reading The Data

This is basically a three step process:

- Open the file.

- Read the file.

- Close the file.

Opening the File

Python provides an open() method, for opening files. When you open a file, you need to tell Python:

- What sort of data to expect, e.g. binary (

b) or text (t). Most AoC programs supply text input. - What you’re expecting to do with the data, e.g. reading (

r), writing (w), or appending (a). I would generally recommend that you only ever read your input data. If you want to modify this data or generate some output, then write it to a new output file.

And thus, to open a text file for reading:

f = open(input_file, mode="rt")

Reading the File

The object returned is a file-like object. There are a few different ways we can read the data and turn it into a useful object we can work with. Here I’ll cover some of the more useful ways in AoC:

# Read all the data in one go, and store it as a single str

input_data = f.read()

# Split the data at each newline, in order to obtain a list of str

data_things = f.read().splitlines()

# And now we can process the data thing by thing...

for thing in data_things:

# do something with thing

Reading Blocks

Here is an example function taken from 2023 Day 5.

It is intended to read data like this:

seeds: 79 14 55 13

seed-to-soil map:

50 98 2

52 50 48

soil-to-fertilizer map:

0 15 37

37 52 2

39 0 15

... etc

The goal is to read the first row into one data structure, and then read the rest as blocks.

def parse_data(data: str) -> tuple[list[int], list[GardinerMap]]:

""" Parse input data, and convert to:

- seeds: list of int

- GardinerMap instances: list of GardinerMap

"""

seeds = []

maps = [] # Store our GardinerMap instances

# split into blocks. Store the first in seeds_line, and the rest in *blocks

seeds_line, *blocks = data.split("\n\n")

assert seeds_line.startswith("seeds"), "First line contains the seeds values"

_, seeds_part = seeds_line.split(":")

seeds = [int(x) for x in seeds_part.split()]

for block in blocks:

block_header, *block_record = block.splitlines() # Split the block into a header row and remaining rows

map_src_type, _, map_dest_type = block_header.split()[0].split("-")

map = GardinerMap(map_src_type, map_dest_type) # initialise our GardinerMap

for line in block_record:

assert line[0].isdigit(), "Line must start with numbers"

dest_start, src_start, interval_len = [int(x) for x in line.split()]

map.add_range(src_start=src_start, dest_start=dest_start, range_length=interval_len)

map.finalise()

maps.append(map)

return seeds, maps

The cool trick here is that when we have a function that returns a list - like splitlines() - then we can unpack the return value across more than one variable. In the example above, one variable is used to receive the first line, and another variable is used to receive all the remaining elements of the returned list.

Closing the File

Having read all the data, we should close the file, e.g.

f.close()

Exception Handling

At any point during opening the file or reading the file, something could go wrong. E.g. maybe you try to open a file that doesn’t exist. Maybe you try to read data beyond the end of the file. Maybe you try to write to a read-only file. So, your program should handle these exceptions. But the good news is… You don’t have to do that yourself!

The Better Way

Python provides a construct called a context manager for dealing with this sort of thing. I won’t get into the details of how a context manager works here. But suffice it to say, this is a better pattern you should use for opening and reading files:

with open(input_file, mode="rt") as f:

depths = f.read().splitlines()

When this block completes, the context manager takes care of closing the file. It also handles exceptions for you.

File Location and Paths

Think about where you want to save your input files, relative to your program. I always put my input files in a folder called input. And that input folder always lives in the same folder as the program itself. Something like this:

Consequently, my AoC programs will always need to read an input file in the relative location input/input.txt. I use Python’s Path object for buildling paths, which are agnostic of the operating system we’re running.

Putting it all together:

from pathlib import Path

SCRIPT_DIR = os.path.dirname(__file__) # get the folder my program lives in

INPUT_FILE = Path(SCRIPT_DIR, "input/input.txt") # get the Path to my input file

with open(INPUT_FILE, mode="rt") as f: # open the input file

data = f.read().splitlines() # read it